What does drought look like?

I tried this once before last year. Optimistically, I engaged some of my readers and encouraged them and myself to go out and photograph the drought, only to realize that it really is much harder than it seems. How many pictures of brown lawns, dried up streams, dead fish, reservoirs near dead pool, or fallowed fields does anyone want to look at? Besides, I have come to the conclusion that this is because in a lot of ways, drought impacts are more human impacts. But, nonetheless, in this fourth year of exceptional drought, I set out last week, camera in hand, and committed myself to posting the results.

And so here they are. Caveat: This is all complicated stuff.

First off, a note. In this post, I’m going to let the farmers tell their story, and intersperse that with my photographic observations. The views of the farmers are their own. This post is not meant to be an endorsement of any of their positions, but more of a glimpse – a cross-section, if you will, of San Joaquin Valley farmers and the landscape on a couple of days in July, in the fourth year of a drought.

California is sometimes described by some in the media as turning into a dust bowl, but if you come to the Central Valley looking for a dust bowl, you won’t find one. In fact, some areas are looking quite well, while others aren’t. Whether or not a farmer has water depends on a number of things: whether or not they have surface water, groundwater, or both; the type of water right they have; and their ability to transfer water all come into play.

I’m headed north from Notebook headquarters in Santa Clarita (perhaps better known as the town where Magic Mountain is), to attend a media event for drought impacts in Kern County, hosted by the Kern County Farm Bureau and the Water Association of Kern County.

First thing I notice as I am driving over the Tehachapis is that Pyramid Lake is green. Eeeew. One of the side effects of the drought is that as water is slowed down and it warms up, there are more algae blooms, some of them toxic.

Once over the hill into Kern County, I head off to see what things look like. Again, I have to say this water stuff is complicated. Looking for a dust bowl? You won’t really find one. What you do find are fallowed fields such as this one …

Once over the hill into Kern County, I head off to see what things look like. Again, I have to say this water stuff is complicated. Looking for a dust bowl? You won’t really find one. What you do find are fallowed fields such as this one …

or this one …

interspersed between other fields still in production, such as these cotton fields …

interspersed between other fields still in production, such as these cotton fields …

It all has to do with groundwater, and Kern County has a fair amount of that. If you have groundwater, you’re in business. If not, well …

It all has to do with groundwater, and Kern County has a fair amount of that. If you have groundwater, you’re in business. If not, well …

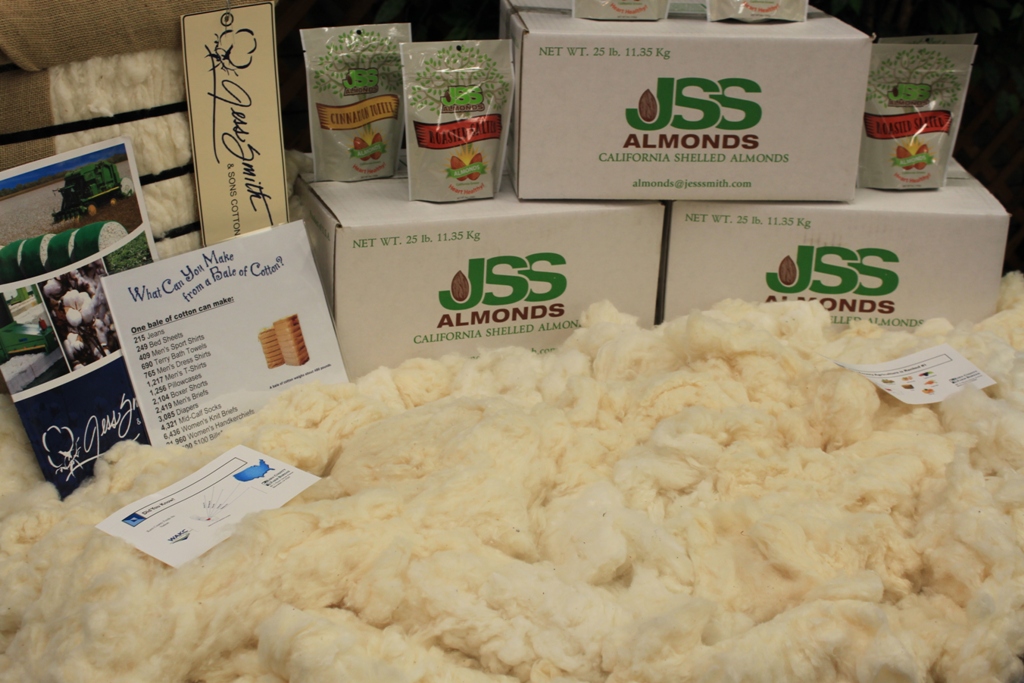

The media event began with a panel discussion, followed by a farm tour. Tables were set up in the back to remind us of the products that come from Kern County – you probably have seen these at your market, maybe even eat them too.

Farmers discussed the impact the drought was having on them:

Farmers discussed the impact the drought was having on them:

Greg Wegis, president of the Kern County Farm Bureau, spoke about the effect of the small allocations from the State Water Project:  “This year we’re at 20%, last year we were at 5% allocations, so we have been drawing on our groundwater supplies. We all know it, and it’s difficult out in the fields to keep the pumps running,” he said.

“This year we’re at 20%, last year we were at 5% allocations, so we have been drawing on our groundwater supplies. We all know it, and it’s difficult out in the fields to keep the pumps running,” he said.

He emphasized the connection between agriculture and the urban populations, reminding of a time not so long ago when the country was primarily agricultural and people had to grow their own food: “We’re looking at a 35-40% increase in population on less water and less land, and so we have to do our part to be more efficient and to continue producing food for generations to come and for the world,” Mr. Wegis said. “We just need to let the general public know and individuals in the urban centers how important it is and that we’re all linked. Agriculture is not separate from their ability to require safe food, and anything that affects us here – a reduction in water supplies will affect food prices, food availability and overall safe food supply that’s grown here in the United States of America.”

Jason Gianquinto, president of the Water Association of Kern County, pointed out that they have not haven’t had an above 60% allocation with the exception of 2011, since about 2005. “So there’s been a number of years that  we’ve been shorted on our surface water supply. Things happen,” he said. “Because of this, we’re not getting the water supply on the surface, so thank goodness we overlie a considerable groundwater basin, but when we don’t have water on the surface, our farmers are forced to go back to the well to keep things going, to keep the crops going. We’ve always talked about, ‘well if they were only growing row crops, it would be easy to shut off that demand, they could just choose to fallow.’ Well we’ve been through that and that’s not a very easy decision. These are family businesses, they have mortgages on their property, there’s a lot of things that are required to be able to keep that farm going, and if you make a fallowing decision like that, it’s basically saying, ‘I’m going to quite farming,’ and that’s not a reality we’re willing to accept today.”

we’ve been shorted on our surface water supply. Things happen,” he said. “Because of this, we’re not getting the water supply on the surface, so thank goodness we overlie a considerable groundwater basin, but when we don’t have water on the surface, our farmers are forced to go back to the well to keep things going, to keep the crops going. We’ve always talked about, ‘well if they were only growing row crops, it would be easy to shut off that demand, they could just choose to fallow.’ Well we’ve been through that and that’s not a very easy decision. These are family businesses, they have mortgages on their property, there’s a lot of things that are required to be able to keep that farm going, and if you make a fallowing decision like that, it’s basically saying, ‘I’m going to quite farming,’ and that’s not a reality we’re willing to accept today.”

Farmer Kent Stenderup pointed out that nowadays only 10% of income goes to food, where in other developed countries, it’s 45%, and even up to 75% in developing or underdeveloped countries.

Kent Stenderup showed a slide of the dried up Lake Isabella and talked about the effect on his family’s farm: “We have 14 wells on the property. Half of our ranch are permanent cr ops; the other half are row crops. Last year, of the 14 wells on our property, in addition to the surface water delivered, we had to lower or work on eight of them. Two of the wells were deemed so inefficient that we had to drill a new well, so those two were replaced by one good new well.” He noted that new wells cost around $400,000 and are much more than a simple business expense as it must be depreciated over 15 – 20 years.

ops; the other half are row crops. Last year, of the 14 wells on our property, in addition to the surface water delivered, we had to lower or work on eight of them. Two of the wells were deemed so inefficient that we had to drill a new well, so those two were replaced by one good new well.” He noted that new wells cost around $400,000 and are much more than a simple business expense as it must be depreciated over 15 – 20 years.

Kent Stenderup says he lowered his wells 60 feet. “I have some neighbors who said, ‘Kent lowered his 60 feet, I’m going to go 80 feet,’ so we’re just getting longer straws and we’re trying to chase the water. We need to work on recharge, we need to develop more storage … ”

Farmer Keith Gardiner, owner of Gardiner Farms and Pacific Ag Management, said the drought has seriously impacted his operations. ““We’re hanging on for dear life,” he said. He said Kern County is well positioned to weather droughts, and blamed environmental regulations for the impacts of the drought. He defended grower’s reliance on groundwater, pointing out they are only trying to protect their livelihoods as well as the ground on which they pay taxes, assessments, and water district taxes on. “They are trying to continue to grow crops for this nation and be profitable and protect their livelihoods. So they’ve resorted to drilling wells all over this valley … We’ve have no other choice. Now that groundwater legislation has come in, it’s going to tell us we’re only going to be able to pump maybe 50%, so we’re all faced with potentially growing 50% of our crops on 50% of our lands.  That isn’t going to work very well. I know we’re not going to be in business, and we’ve been in business 65 years.”

That isn’t going to work very well. I know we’re not going to be in business, and we’ve been in business 65 years.”

“The real story, in my opinion, we have taken water that the farmers built all the infrastructure in the 60s … … We’ve paid for 100% of our water and gotten as little as 5% or none, but we still continue to pay our share of that bill. So the takeaway from this in my opinion is the loss of the water through the Delta. Strictly an environmental decision that Judge Wanger made a few years ago, and this county and many other counties in this state are going to go dry if that decision isn’t reversed legislatively in Washington DC, and in the state of CA.”

Farmer Andy Pandol said that they are all one pump failure away from economic disaster. “Probably one of the bigger things is how do you get the wet water from the well to a vineyard to a plant on any given day, and I have to do this on a daily basis, and that’s my life,” he said. “We have wells that are adjacent to the water district’s distribution system so on any given day we are irrigating with a well and maybe we’ll have some extra capacity, maybe it can flow to the district to be distributed, it’s a real challenge because you have so many places that need water now. What I have extra in one spot and where am I short, what are my options … and then you get the neighbors. ‘You gotta help me, I’m dying over here. The pump company won’t show up for three or four or five weeks, this fruit is just about ready to pick, can you help me?’ Well, you kind of have to help him. ‘OK I can give you this.’ ‘How am I going to pay you back?’ ‘I don’t need your money, I need your water … “

Farmer Andy Pandol said that they are all one pump failure away from economic disaster. “Probably one of the bigger things is how do you get the wet water from the well to a vineyard to a plant on any given day, and I have to do this on a daily basis, and that’s my life,” he said. “We have wells that are adjacent to the water district’s distribution system so on any given day we are irrigating with a well and maybe we’ll have some extra capacity, maybe it can flow to the district to be distributed, it’s a real challenge because you have so many places that need water now. What I have extra in one spot and where am I short, what are my options … and then you get the neighbors. ‘You gotta help me, I’m dying over here. The pump company won’t show up for three or four or five weeks, this fruit is just about ready to pick, can you help me?’ Well, you kind of have to help him. ‘OK I can give you this.’ ‘How am I going to pay you back?’ ‘I don’t need your money, I need your water … “

Here we are stopped at a pump station, and a representative from South San Joaquin Irrigation District is explaining how he is routing grower Andy Pandol’s water around through SSJID’s distribution system, not only to water his crops, but to help out his neighbors, too. ‘”I’m not unique. There are lots of guys doing this,” said Andy Pandol. “You’re parlaying your water around … that’s what we’re going and that’s what you have to do, and it’s on a daily basis. It’s just like living from paycheck to paycheck. You’ve got so much and you have to cut and shave every day and you have to defensibly irrigate … ”

Here we are stopped at a pump station, and a representative from South San Joaquin Irrigation District is explaining how he is routing grower Andy Pandol’s water around through SSJID’s distribution system, not only to water his crops, but to help out his neighbors, too. ‘”I’m not unique. There are lots of guys doing this,” said Andy Pandol. “You’re parlaying your water around … that’s what we’re going and that’s what you have to do, and it’s on a daily basis. It’s just like living from paycheck to paycheck. You’ve got so much and you have to cut and shave every day and you have to defensibly irrigate … ”

Here are a few shots of the pump station …

The pump station is located alongside the Friant-Kern canal. This reach of the canal isn’t being used much; the water level here is quite low and not moving. The pump station is moving groundwater around instead. Andy Pandol tells me that further up north, they are running portions of the Friant-Kern canal in reverse in order to get water to where it needs to go.

At Pandol Farms, grapes are now being harvested.

At Pandol Farms, grapes are now being harvested.

These are table grapes, the black seedless variety.

These are table grapes, the black seedless variety.

It’s almost like a small city out here when they are harvesting.

It’s almost like a small city out here when they are harvesting.

These grapevines are very tall – I can easily walk underneath them. The temperature is much cooler under here, too.

These grapevines are very tall – I can easily walk underneath them. The temperature is much cooler under here, too.

The farm tour now over, it was time to continue on.

The farm tour now over, it was time to continue on.

Drought impacts were what I was searching out, and with reports all this groundwater being pumped, I headed north to the areas where the subsidence is reported to be the worst.

Along the way, I passed the Friant-Kern Canal, much fuller and moving water as opposed to the lower reach. This part is probably running backwards.

Heading northeast up the valley, I passed canals that were full as well as ones that weren’t. Again, not everyone is without water. This drought stuff is complicated!

Heading northeast up the valley, I passed canals that were full as well as ones that weren’t. Again, not everyone is without water. This drought stuff is complicated!

The Russell Street bridge near Firebaugh is in the area where subsidence is at some of the highest rates in the state. You can see how the low the bridge is to the water; there is no space, or ‘freeboard’ between the water surface and the bridge. To prevent flooding, side walls had to be built on to the bridge.

The Russell Street bridge near Firebaugh is in the area where subsidence is at some of the highest rates in the state. You can see how the low the bridge is to the water; there is no space, or ‘freeboard’ between the water surface and the bridge. To prevent flooding, side walls had to be built on to the bridge.

This is Check Station 18 on the Delta Mendota Canal. Although you can’t necessarily see it, the check station and the gates had to be modified due to subsidence. The buckling on the side is likely due to subsidence, although the USGS can’t say for sure.

This is Check Station 18 on the Delta Mendota Canal. Although you can’t necessarily see it, the check station and the gates had to be modified due to subsidence. The buckling on the side is likely due to subsidence, although the USGS can’t say for sure.

It’s getting on in the day, and so although I had planned to go through El Nido, a nearby town that had reportedly been experiencing subsidence impacts, it’s time to head north to Sacramento.

It’s getting on in the day, and so although I had planned to go through El Nido, a nearby town that had reportedly been experiencing subsidence impacts, it’s time to head north to Sacramento.

On the return trip, headed down I-5, around Patterson and Newman, things on this side of the valley look pretty good. Here is where some of the oldest and therefore most assured water rights in the valley are, and looking out at the landscape, there are a lot of fields in production. This isn’t the case further south.

A little further down the road, I exit at Los Banos and head east into the valley.

A little further down the road, I exit at Los Banos and head east into the valley.

Los Banos is one of the original settlements in the San Joaquin Valley, established around 1840. It was home to Henry Miller, who was at one time considered the largest landowner in the U.S. His company, the Miller and Lux Company, transformed the Central Valley and could be considered perhaps a precursor to corporate farming.

I hadn’t driven through this area before, and having done so, I highly recommend it. Nice farms and fields, neatly tended.

I hadn’t driven through this area before, and having done so, I highly recommend it. Nice farms and fields, neatly tended.

The canals here were full and the fields green.

The canals here were full and the fields green.

I decided to pay a visit to Cannon Michael (twitter followers will know him as @agleader) of Bowles Farming Co. and traveling down “Henry Miller Lane”, I know these are some of the oldest water rights in the valley, practically rock solid. They are first in line.

I decided to pay a visit to Cannon Michael (twitter followers will know him as @agleader) of Bowles Farming Co. and traveling down “Henry Miller Lane”, I know these are some of the oldest water rights in the valley, practically rock solid. They are first in line.

But in these years of exceptional drought, even these farmers with the oldest rights only received 45% of their water this year. Cannon Bowles has had to fallow 3,000 of the 11,000 acres on his farm. “With the historic water right that we have, we had access to some surface water – many farms around us did not have any access at all, so we were in a fortunate position to get some water,” Cannon Bowles tells me. “Based on our drip irrigation systems and some wells and reuse system in our district, we were able to farm about the most that we could, about 65% of the farm we were able to grow a crop on. We’re just finishing up now and might be a little short of water so we might see some yield reductions, just trying to finish the crop.”

Some fields he simply abandoned, letting his neighbors sheep and cows graze on what’s left.

Some fields he simply abandoned, letting his neighbors sheep and cows graze on what’s left.

“A little bit frustrating this year is that we’re going to end up the water year with more water in the major storage reservoirs like Shasta, more water in the reservoir than what we started the year with,” he said. “In previous droughts like 1977, additional water had been released through the summer months when demand was highest for agricultural uses and communities and for wildlife refuges, and this year, that really was not done. There’s going to be over 1 million-plus acre-feet of water in storage at the end of 2015 then there was at the same time in 1977. So it’s an issue. Obviously the fish issues and the concerns over cold water for winter run salmon seem to kind of trump everything now, including water rights.”

“A little bit frustrating this year is that we’re going to end up the water year with more water in the major storage reservoirs like Shasta, more water in the reservoir than what we started the year with,” he said. “In previous droughts like 1977, additional water had been released through the summer months when demand was highest for agricultural uses and communities and for wildlife refuges, and this year, that really was not done. There’s going to be over 1 million-plus acre-feet of water in storage at the end of 2015 then there was at the same time in 1977. So it’s an issue. Obviously the fish issues and the concerns over cold water for winter run salmon seem to kind of trump everything now, including water rights.”

Nonetheless, farmers are optimists, Cannon tells me. “On the farm, we’re continuing to put in the drip irrigation and solar systems and other positive projects and definitely with the hope that we can continue to farm and continue to safely and ethically produce food and fiber for the state of California, the rest of the nation, and in some cases, the world,” Cannon Bowles said.

Nonetheless, farmers are optimists, Cannon tells me. “On the farm, we’re continuing to put in the drip irrigation and solar systems and other positive projects and definitely with the hope that we can continue to farm and continue to safely and ethically produce food and fiber for the state of California, the rest of the nation, and in some cases, the world,” Cannon Bowles said.

Heading further south, more towards the central portion of the San Joaquin Valley, the water rights are not so assured, and the impacts more obvious.

Fallowed fields …

And dry and soon to be downed …

And dry and soon to be downed … And yes, paradoxically, new ones, too …

And yes, paradoxically, new ones, too …

A lot of protest signs around …

A lot of protest signs around …

This area is just north of Kettleman City. Agriculture in this part of the valley looks different than Los Banos. Gone are the farmhouses and barns that dot the landscape; instead just fields and orchards for miles and miles.

This area is just north of Kettleman City. Agriculture in this part of the valley looks different than Los Banos. Gone are the farmhouses and barns that dot the landscape; instead just fields and orchards for miles and miles.

The reliance on groundwater here is obvious. Groundwater pumps everywhere.

The reliance on groundwater here is obvious. Groundwater pumps everywhere.

As in Kern County, pipes are routing water from field to field.

As in Kern County, pipes are routing water from field to field.

This is the view from Kettleman City looking northeast towards the area I had just driven through. Here, the dry fields in the distance are much more noticeable.

This is the view from Kettleman City looking northeast towards the area I had just driven through. Here, the dry fields in the distance are much more noticeable.

From here, it’s back to Notebook headquarters …

From here, it’s back to Notebook headquarters …

So that’s the cross-section of the San Joaquin Valley at the end of July in 2015. A little dusty in some areas, but not a dust bowl and farmers helping each other out.

For more information on all of these water issues, check out my other blog here: www.MavensNotebook.com.

So long from the San Joaquin Valley!

Seems like photos of bulldozed/dying almond trees are often used to convey the severity of CA’s drought. For good reason, too; they’re compelling. But they can be misleading. Almond trees have an average lifespan of 20-25 years (per the AG Marketing Resource Center at http://www.agmrc.org/commodities__products/nuts/almond-profile/ ), so one can expect trees of that vintage to be bulldozed each year even during the wettest years. CA planted about 13,000 acres of new almonds in 1990, so we can expect about that much to be bulldozed this year, drought or not. Over 31,000 acres were planted in 1995, so if the lifespans were closer to 20 years, one would expect about that much to be bulldozed this year. (That’s a lot of trees.) While it’s distinctly possible that the trees in the above photos were indeed being taken down purely for drought-related reasons, the viewer really doesn’t know.

Many striking photos are used in the media these days to communicate CA’s difficult water situation. As the Maven noted, “water in CA is complicated” — a good reminder for all of us readers/viewers to be vigilant.

(almond acreages found at: http://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/California/Publications/Fruits_and_Nuts/201504almac.pdf )